21st Century Nesting Practices has developed over a five-year period (2012 – 2017), including a one-year Residency and solo exhibition at Harcourt House Artist-Run Centre in Edmonton, and further exhibitions at Fleishman Gallery, Toronto, in ‘At Odds’ at Art Gallery of St. Albert, and as part of ‘Elsewhere’ at Gallery @ 501 in Sherwood Park AB. For the most recent exhibition at the McMullen Gallery, I am presenting new video and audio work arising from further research and work in sound and installation, including my own field recordings and some from the Cornell Ornithology Library, used with permission & deep thanks for their support.

21st Century Nesting Practices considers the human penchant for investing objects in the material world with significance – most specifically, this work explores the tangible reality of specific objects and its relationship to what those objects may signify psychologically or emotionally to people. Gaston Bachelard observes that

“A nest-house is never young. … For not only do we come back to it, but we dream of coming back to it, the way a bird comes back to it, or a lamb to the fold. This sign of return marks an infinite number of daydreams, for the reason that human returning takes place in the great rhythm of human life, a rhythm that reaches back across the years and, through the dream, combats all absence.” (from Gaston Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space, chapter 4)

While Bachelard offers some useful insights here, I also find his analysis almost willfully incomplete. It dismisses the idea that the association between ‘nest’ and ‘home’ could simultaneously resist and embody longing or absence, through the very object from which the associations come. This provoked a several-years-long field of inquiry for me, toward understanding the connections between the actual process of making (and re-making) nests that birds enact, and human resilience.

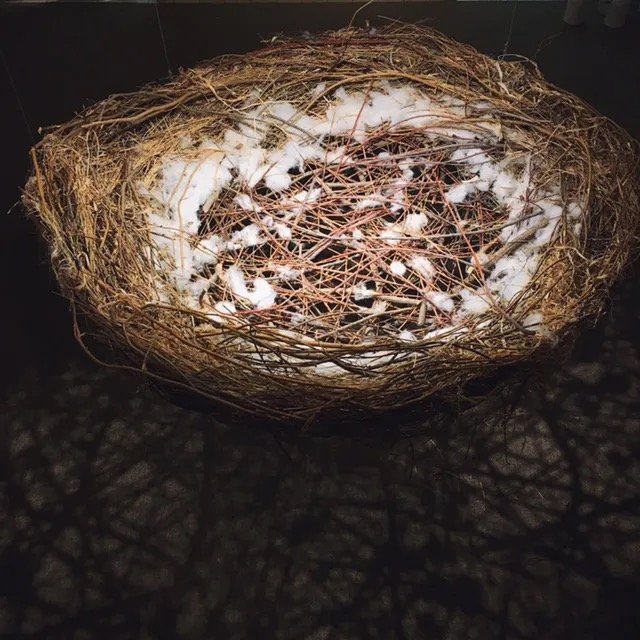

What of the tenuous nature of the nest itself? In human terms, nests are deeply evocative of security, warmth, comfort, home, and family. The reality of the nest-as-object is, however, contingent and often precarious: it is at once a source of protection and exposed to the elements, subject to the potential for destruction at any point. Does this apparent contradiction not speak on some deeper level to a visceral human understanding of the simultaneous fragility and necessity of both emotional and physical spaces of rest and safety?

The ‘mind-nest’ each person creates is continually rebuilt and edited through the conjoined filters of time, context, and experience. It is also thoroughly conditioned by the narratives of place, belonging, and family as they are inscribed on individual, specific bodies. Thus, while Bachelard can contend that “when we examine a nest, we place ourselves at the origin of confidence in the world,” this is true only insofar as the individual’s personal history at a given point can allow. (from Gaston Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space, chapter 4)

How resilient the human spirit, then, that has the capacity to build and rebuild ‘nests’ from which to draw sustenance of all types.

NEST comprised earlier work and experiments in developing this body of work, and considered these same questions from a darker, more difficult space: a position of personal grieving, and wrestling with the emotional healing needed to find understanding and compassion in the face of less-than-ideal memories and experiences. In these earlier iterations, this work took Bachelard’s ideas and parsed them to expose the assumption that the association between the ideas ‘nest’ and ‘home’ would be consistently positive.

What if those childhood narratives have been called into question as unverifiable, or are suspect in some way?

What if that sense of security (of any sort: emotional, physical) within the primal nest held no guarantee; what if it was a contingent thing, qualified or tenuous in some way?

These other possibilities disrupt the understanding of the nest as refuge and haven, home for the heart and body … and lead to a second set of questions: what effect does this have on the way we construct our self-story through the filters of memory, and in relation to the assumptions inherent in the social discourse of race and class and gender?

This body of work developed over time, and reveals a trajectory of gestures toward re-imagining the relationship between people and these (and other) objects, toward understanding the connections between the process of making and the process of recognition.

Sydney Lancaster, January 2018

The galleries below show the work developed for NEST & 21st Century Nesting Practices, in various exhibition settings.

New work was developed for each iteration.

I gratefully acknowledge the support of the Alberta Foundation for the Arts for supporting the development of the work for the Exhibition at McMullen Gallery.